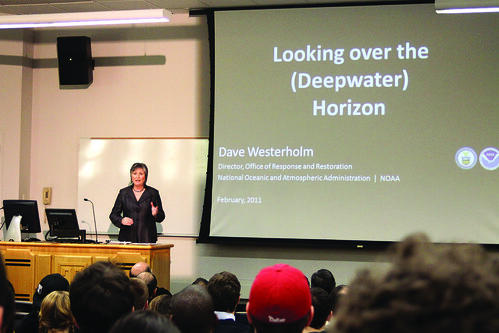

Dave Westerholm discusses the response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Dave Westerholm, the director of the Office of Response and Restoration of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, came to Temple on Feb. 23 as the keynote speaker during National Engineers Week. Westerholm spoke concerning his department’s role in the emergency response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill last April.

Westerholm highlighted the need for improved technology to better aid Gulf Coast recovery efforts, while praising both the work and aspirations of student engineers such as those in attendance.

“Not only are engineers the cause of the problem, but they are also the solution,” Dr. Keya Sadeghipour, the dean of the College of Engineering who spoke briefly to students in attendance, said.

Westerholm concentrated his talk on explaining efforts put forth by the NOAA to assess environmental impacts of the spill and the preventative measures currently in place to stop similar incidents from occurring.

Behind these efforts are scientists and engineers trying to better understand how oceanic currents operate beneath the water’s surface.

“There’s still a lot of mystery as to what goes on a mile beneath the surface,” Westerholm said.

The Deepwater Horizon drilling rig was located so deep on the sea floor that little could be done to disperse the tons of oil spilling into the water.

“I’d say that between 25 and 50 percent of the oil was spreading out before it even reached the surface,” Westerholm said.

This oil then spread underwater, approximately 50 miles outside of the initial spill zone.

“This was one of the first times we had to assess oil damage that deep and widespread beneath the surface,” Westerholm said.

He explained that before the spill in the Gulf Coast, very little technology was available that could effectively disperse oil particles’ “subsurface.”

The only step taken toward developing a subsurface oil dispersant was found in an unpublished paper that “supposed” how such a substance could be created, he said.

Westerholm added that it took time to address public concerns that arose during the oil spill and clear up confusion that still exists.

In the age of social networking, where Twitter and Facebook have dramatically increased the public demand for up-to-date information, Westerholm said his department fell behind.

“We weren’t prepared to push information to the public in a timely manner. There was a lot of misinformation during the spill that we did our best to clarify,” Westerholm added. “If you don’t put [information] out, someone else will. Then you spend more time correcting false facts than giving them.”

Westerholm said he hopes the events and reaction to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill will help develop a faster, more comprehensive emergency response to such catastrophes, and contribute to a better understanding of underwater ecosystems.

Chase Grier can be reached at robert.grier@temple.edu.

That’s a misleadingly-captioned photo you’ve got there!