I used to joke about being a statistic.

Self-deprecation has always come naturally to me in a lot of different ways, like how I handle breakups, but you wouldn’t think I’d try to find humor in someone assaulting me.

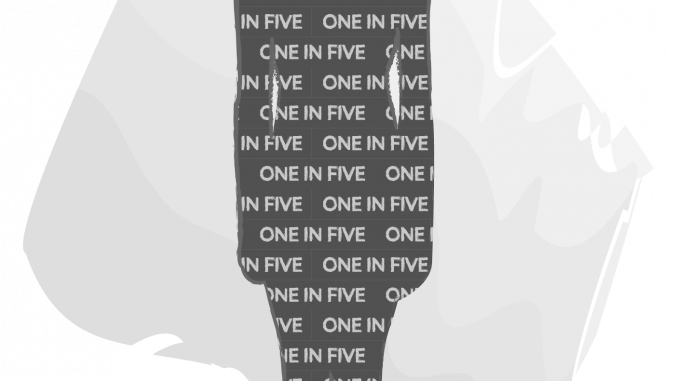

One in five women will be sexually assaulted in college, according to a 2015 report from the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

More than 50 percent of college sexual assaults happen in August, September, October or November, and students in their first and second semesters of college are at a higher risk of sexual assault than others, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network.

Less than one week into my freshman year — before I had even taken my first class — I was sexually assaulted.

It was by someone I knew. Someone I thought might become a friend.

I can still recall his Johnson Hall dorm room. We were sitting on his bed and listening to music when he abruptly shut the computer screen. There was silence, and then he forced himself on me.

I said “no.” There’s no debating that. I said “no” multiple times, but that didn’t stop him. It took me screaming and pushing him off with all of my strength for him to stop.

As a guest in his dorm, I felt completely trapped. I was able to get out of his room, but I was too scared of getting him — someone who had just committed a sexual crime against me — in trouble.

I didn’t know very many people at Temple yet, but that night I was able to make contact with a new friend, who sat with me as I recounted what happened. I remember I couldn’t stop shaking. I hugged myself, acting as my own consoler in a way, but also trying to get rid of the control he had over my body.

I slept in a high school acquaintance’s dorm room in Johnson Hall that night. I spared her most of the details. I just told her someone made me uncomfortable, because, in that moment, I felt like telling my side of the story was too complicated. No one was interested in hearing about the freshman who was sexually assaulted days after moving in.

“Where did you go?” he asked me the following morning when he signed me out of Johnson Hall.

“You made me feel unsafe after I repeatedly told you no,” I managed to whisper.

“Oh.”

That short-lived conversation is embedded in my memory of that night. His lack of response made me feel like what happened wasn’t a big deal, like I shouldn’t take what happened to me so seriously.

And so I didn’t. If I played it off as a bad hook up, then it could never be trauma for me.

As my first semester progressed, I found my core group of friends, the people I consider my best friends to this day.

Because we had mutual friends, I often saw my abuser at parties and my friends would even play music at his house shows sometimes. Whenever I saw him, I could feel myself sinking non-consensually into his bed again. But I pretended it didn’t bother me. And with time, I forgot that it even happened, playing into the stigma of shame that surrounds sexual assault.

It can be easier to play off sexual assault as “normal” than to get help, because getting help and having someone actively listen to your story is often nuanced and filled with doubt.

Last month, Temple partnered with Women Organized Against Rape to open a satellite office on Main Campus, so survivors of sexual assault can visit at any hour of the day. This large and important effort made me start to think about that August day during freshman year again.

It took two years for me to understand how much the avoidance of my sexual assault has played into the stigma and victim-blaming linked to the issue within society.

I should have reported him to his RA that night. I should have called Tuttleman Counseling Services the day after. And in the months after, I should have told my friends that it was not OK for them to associate with my abuser.

But at this point, I can’t beat myself up for not doing those things, because reporting sexual assault on a college campus is frowned upon at schools across the country — from Baylor University in Waco, Texas to the University of Montana in Missoula, Montana, which have both been accused of mishandling sexual assault cases involving their football teams.

If more survivors can feel comfortable telling their stories, then there may be less need to treat sexual assault as a taboo topic. It needs to be discussed, and not brushed off in the way I treated my experience. This way, the understanding of “no” and the importance of consent can be at the forefront of the dialogue.

There’s strength in being a statistic. I’m not alone, and I never will be. There are hundreds, if not thousands of survivors who walk Main Campus, just like me. Some of them have to face their abuser often, just like me.

And this time, I’m no longer hiding from my assault in my own shadow.

Emily Scott can be reached at emily.ivy.scott@temple.edu or on Twitter @emilyivyscott.

Be the first to comment