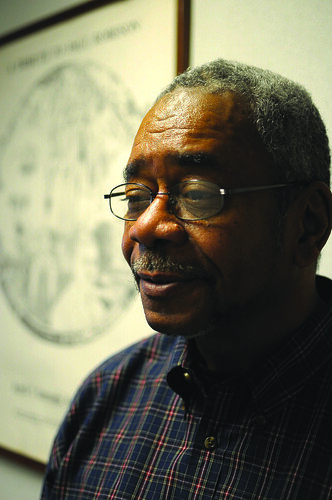

Assistant African-American studies professor Dr. Maxwell Stanford has a rich history. The West Philly native helped form the militant black organization, the Revolutionary Action Movement in the 1960s and worked with historical figures such as Ella Baker, Thomas Higginbotham and Malcolm X. He recounts his roots, his journey through the 1960s African-American civil rights movement and his advice for those looking to carry on the mission for human equality.

The Temple News: You’re an expert on African-American history. When did you first develop this interest, and when did you feel obliged to get involved in black social and political movements?

Maxwell Stanford: My interests were developed because of my parents. I come from a very political family. I’m blessed for the mother and father I had. My father especially had a lot to do with the nurturing of my political consciousness. I went to move with him at age 16, and I would always listen to conversations between him and Thomas Higginbotham, who was president of the Philadelphia [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] at the time. I met a lot of influential people with him and was taken places and saw things the average teen didn’t.

Then, when I transferred schools, I was accidentally put into an advanced history class. My history teacher told me and the only other black student in the class, “The problem is that I’m white and Jewish and I know more about black people than you.”

I knew he was wrong, but that really got me interested in learning more about history too. I started reading a lot and finding context through books. I gained a more African-centered perspective. And that perspective was crystallized once I went to Central State College [in Wilberforce, Ohio] because there were professors with thorough knowledge of these topics.

TTN: Can you describe some of your experiences as a political and social activist?

MS: At Central State, I got involved with the Congress of Racial Equality organizing freedom riders. Then in 1963 and 1964 I worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In 1964 I was sent to Nashville for an African-American student conference on black nationalism. I also went to Detroit in 1964 for a conference and that’s when we took [the Revolutionary Action Movement] from a student organization to a national one. I also helped form the New York Black Panther Party, which was the predecessor to the Black Panther Party for Defense. I was able to work with and learn a lot from people like Ella Baker, Ethel Johnson and Malcolm X.

TTN: What was your relationship with Malcolm X like?

MS: He was like a brother or uncle to me. I had met him in 1962 and remained in close contact with him throughout 1963. I remember when I was attacked and arrested in May 1963 on 31st and Dauphin streets by the police led by Frank Rizzo. We were demanding the inclusion in the building trade of African-American workers, which is still a problem that persists today. I called Malcolm from the police station on 19th Street and Montgomery Avenue and he helped us get over 1,000 people to demonstrate in that area. When I was sent to New York to recruit Malcolm to RAM he kept me with him for eight hours a day for a whole month, and I learned so much from him during that time. I met with Malcolm about 15 days before his assassination and that was the last time I saw him.

TTN: Can you describe how it feels to have a cemented place in history, knowing that your exploits are written about in books and journals and many consider you a pioneer of black rights?

MS: Not really. I don’t see myself that way. I’m just a servant of the people and a servant of Allah. I don’t separate the two. I just think that the pursuit of happiness, equality, freedom and justice is the overwhelming will of the majority of people on planet Earth. And the will of God is that we live in an equalitarian society free from hunger and want. We have the ability to reach that level, but it’s all intertwined with human rights.

TTN: What would you say to black students who are dedicated to furthering the progress of racial equality and justice and carrying your torch, so to speak?

MS: I would tell them that the struggle goes from the cradle to the grave and from one generation to the next until we win; until racism, classism and sexism end. You have to be focused and the earlier you become focused the better. Don’t allow yourself to be bamboozled by this gangster rap and this “monster” mess that has been presented to you. It’s all designed to derail you from your potential. We all have to become more united regardless of race, regardless of religion and decide where we want this society to go. A people united cannot be defeated.

Angelo Williams can be reached at angelo.williams@temple.edu.

Georgia Prison Strike Sets Agenda for Future Struggle

By Tom Big Warrior

For years the courts have been dodging the issue of the constitutionality of the exemption clause of the 13th Amendment. Comrade Jalil and Comrade Spider both presented good arguments that challenged the legality of prison slavery based upon the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (authored by the U.S.) which prohibits slavery and compulsory labor under any circumstances. But the courts refused to hear them dismissing their petitions as “frivolous” lawsuits. But now, after the “Largest Prison Strike in U.S. History,” the term “frivolous” hardly applies.

The Georgia prisoners are arguing that forced prison labor violates the 13th Amendment which outlawed slavery in the U.S. This forces the state to bring up the exemption clause, which continues slavery for “those convicted of a crime.” If the Court supports this, it calls forth an abolition movement to amend the 13th Amendment. If it rules that it is unconstitutional, it opens the door to defining what rights (as citizens) prisoners do have.

If they are citizens, what rights of workers and workers’ protection legislation apply? Do they have a right to a minimum wage? Do they have the right to collectively bargain? Do they have a right to vote? Do they have a right to free speech and to communicate with one another and to peaceably assemble and petition, and in general to organize?

The whole idea of the prison-industrial complex rests on the ability to super-exploit prisoners for little to no wages and pass the cost of their maintenance onto the tax-payers. If paid a “livable wage” as the GA prisoners demand, the incentive for mass incarceration goes out the window. The alternative for prison slavery is not sitting in cells but going home en masse.

The tactic of voluntary lock-down is powerful. They can’t claim the security of the institution is being threatened. Any violence that results is guard-initiated and the violence of the slave-master. It serves no “legitimate” security interest.

The key to the success of the tactic is full participation of the prisoners. The strength of unity is pitted against the injustice of the system. It is a proletarian way of fighting – like the sit-down strikers at the Flint GM plant that established the UAW.

One thing you always hear from prisoners is that “these guys here are too divided by race, religion and gang affiliation to accomplish anything.” But where are the race divisions greater than Georgia? Yet it was the leaders of these sub-divisions that organized the strike. They became the “shop stewards” of the de-facto “union.” Poor white, Black or Latino, Rasta or Muslim, Blood or Crip, they led their brothers as a class – the proletarian class – showing just how powerful that is.

Not-for-nothing is the proletariat called the “class of the future.” Only the proletariat is capable of leading society beyond the Epoch of Exploitation to a new epoch based upon social justice and equality for all. The attempted media black-out of news on the GA prison strike reflects how seriously the capitalist-imperialist system was challenged. Silence often speaks loudest. Their fear was not just of the strike spreading to other Georgia prisons and other state prison systems but of the lessons that could be drawn by the oppressed everywhere.

The handful of super-rich “fat cats” running the world are no match for the power of the people united. The reality is the only thing keeping us down is our disunity and intimidation — our lack of consciousness. We could all be free and enjoying the fruits of our collective, socialized labor without their boots on our necks. We can sweep away poverty, war, oppression, and yes – crime itself – if we come together and stand up as a class.

The strategy of the United Panther Movement (led by the New Afrikan Black Panther Party – Prison Chapter) is based on building people’s unity and people’s power. From transforming the “slave pens of oppression” into “schools of liberation” to transforming the oppressed communities into “base areas of cultural, social and political revolution in the context of building the worldwide united front against capitalist imperialism,” we are moving towards a solution to all our problems – and the solution is world proletarian socialist revolution!

The fight for prisoners’ human and democratic civil rights is an important part of this fight. For what is communism but the extension of human rights to include all human needs?

Dare to Struggle Dare to Win!

All Power to the People!