Jonathan Gerstenhaber wants to make medical devices more personal. That’s what he did by developing 3D-printed bandages.

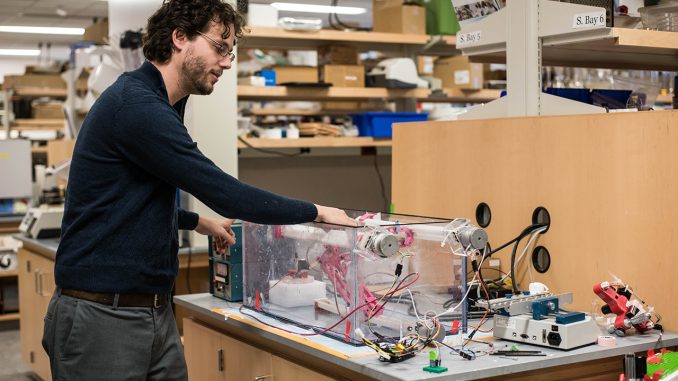

Gerstenhaber, a bioengineering professor, along with the help of other engineering faculty and students, created a 3D printer that uses electrospinning technology to print bandages directly onto a patient’s skin, making them fit the individual’s physical form.

Electrospinning technology is a production method used to make polymer fiber, which is a synthetic material.

On March 25, Gerstenhaber presented a demonstration of the prototype — which consists of a larger robotic piece made from additional 3D-printed components — at The Franklin Institute.

Gerstenhaber drew inspiration from a presentation made by Peter Lelkes, the bioengineering department chair, while he was pursuing his Ph.D. in bioengineering at Temple last year. He said Lelkes’ work focused on bone regeneration using fabrics made from cytosine, one of the bases found in DNA.

“What he found was that suddenly he had an ability to lay these fabrics on holes drilled in skulls of mice, and they could heal them,” Gerstenhaber said. “[The holes were] big enough that they wouldn’t [normally] heal on a mouse.”

When Gerstenhaber saw the presentation, he started to think about individualizing dental and jaw implants, many of which are standardized.

“All of their implants were either flat, or perfectly round, something they could do without having a complicated robot do it for them because they were limited,” Gerstenhaber said. “[Prosthetic companies] couldn’t make any realistic examples of any of these use scenarios because the tools didn’t exist.”

Branching off from Lelkes’ project, Gerstenhaber wanted to develop a flexible bandage for serious wounds that would not only stop bleeding, but also quickly regenerate the skin.

“I was like, ‘Wow, I’m making this tool to make my life easier, but it’s going to open this whole new avenue of research,’” Gerstenhaber said.

His bandages are made with a soy protein, which helps tissue heal faster than it would if covered by a conventional bandage. The technique is being researched in labs within the College of Engineering. The participating scientists are testing the bandages to ensure they have the capability of helping external tissue regenerate.

When applied with water, the white bandages adhere to the skin in an almost invisible fashion. Then, when the patient moves, the bandage moves with them, almost as though it were part of their skin.

“We’ve mainly been looking at burns, and the sorts of wounds that don’t heal well, and when they heal, they sort of heal like very bad skin,” Gerstenhaber said.

Some other bioengineering professors, as well as undergraduate and graduate students, have contributed to the project under the supervision of Lelkes and bioengineering professor Yah-el Har-el.

Baran Arig, a sophomore bioengineering major, started working on the bandage project as a freshman.

Arig, who conducted research on electrospinning in high school, said he wanted to continue his study of the technology.

“For the most part, what I am doing is I am making a viscous solution for the electrospinner,” Arig said. “I am spinning these solutions to create these electrospun scaffolds that can be looked at through a microscope.”

In addition to the main printing prototype, Gerstenhaber and his colleagues have also constructed a modified, handheld version of the 3D printer. The handheld printer is closer to being ready for market than the full-size 3D printer.

The larger version is still undergoing some alterations to improve its efficiency. Personalizing the bandages requires a time-consuming scan of the targeted area.

Gerstenhaber said he hopes that in the future, the handheld model will become a household staple, but for now he and his team are focused on bringing it to market.

While Gerstenhaber recognizes all medical devices, like physical implants or skin grafts, are important, he said tissue regeneration is the greatest solution to healing wounds.

“If I can allow your body to heal itself, that’s really the best thing I can give to you,” Gerstenhaber said. “Especially if that healing is natural and is complete.”

Be the first to comment