Through the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, students help prove Pennsylvania inmates not guilty.

Theresa Giamanco looked at the looping script scrawled on several sheets of yellow notepad paper – so many sheets that it must have taken the author hours to write by hand.

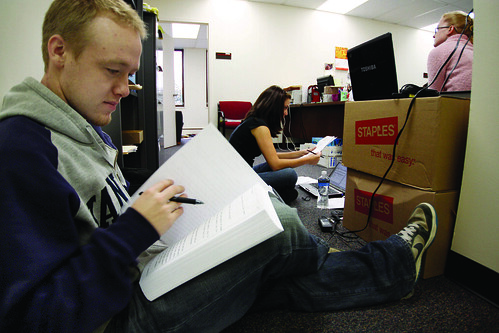

“You can tell people put a lot of time in hoping to get our attention,” Giamanco, a third-year law student, said. As part of a clinical studies requirement at Temple’s Beasley School of Law, she works at the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, housed by Temple in an office of the University Services Building.

The project may be modest in size, staff and budget, though its mission is anything but. It works to free innocent people wrongfully convicted of crimes, currently serving lengthy sentences in Pennsylvania prisons. The project relies on students to provide most of the manpower.

“It’s surprising how much the inmates know about the law,” third-year Temple law student Mary Hoang said. “Some of the stuff they point out, like certain procedures and case law, are things that I don’t even remember. They know it all so much better than us because it’s their life.”

Inmates must seek out the Innocence Project for help by sending a letter stating how they are innocent. Students read each letter, deciding which qualify for the next step. On any given day, a 6-inch stack of letters can sit on a shelf, waiting to be read.

“[Since April], we heard from over 1,000 inmates, and 500 cases are under further consideration,” Legal Director and Innocence Project Adviser Marissa Boyers Bluestine said.

The project only works with inmates who are factually innocent. Third-year law student Stephen Rudman said he likes working on the first stage the most.

“That’s what this is all about,” Rudman said. “It’s you and a letter … is it possible he didn’t do it?”

Cases also have to be in Pennsylvania and past the appeals process. Inmates must be serving lengthy sentences for robbery, rape or homicides.

If the case meets those requirements, it moves to the second and third stages, which require more investigative work. Inmates send all the information pertaining to the case and fill out questionnaires.

“I’m always shocked at the trial transcripts,” third-year Villanova law student Maureen Belluscio said, pointing to a court transcript she was reading. Notes lined the margins.

“We got transcripts from an inmate, and his notes are on the side as to what he’s thinking,” Belluscio said. “It’s interesting to see cases … from this view.”

In stage three, students build a case for the inmate’s innocence.

“Stage three is the gritty stuff,” third-year Temple law student Noor Taj said. “You get to pretend you’re an investigator, and you start unraveling the case. It’s kind of fun.”

Students enjoy the hands-on approach, which gives them the opportunity to handle several cases in a variety of stages. The downside is that students don’t get to see one case from start to finish.

“The time frame is kind of annoying because there’s little we can do in four months,” Rudman said. “In the case I’m working on, we’re doing a Post-Conviction Relief Act, which was filed in May 2005, and it’s still in the initial stages. It’s a very complicated case.”

His case involves a death-row inmate, a mistrial, a jailhouse snitch, a police sketch that “looks nothing like him” and neighbors who identified someone else as the perpetrator, Rudman said.

In comparison to his peers, third-year Villanova law student Russell Williams got to experience a thrilling part of the Innocence Project – exoneration.

Last summer, Williams interned at the Connecticut Innocence Project. In August, inmate Kenneth Ireland was absolved for rape and murder after serving 21 years in prison. It furthered his interest in the project and criminal defense law.

“As soon as it popped up at Temple, I knew I absolutely wanted to do it,” Williams said.

Interning at the Innocence Project is part of an elective class that fulfills law students’ clinical studies requirement. The class is also open to Villanova law students like Williams and Belluscio.

Students don’t have to be in the class or in law school to intern.

“We can always use more volunteers,” Bluestine said. “We get 100 letters per week. We have a lot of work to do.”

Non-law students work only in stage one, reviewing inmates’ letters because stage two and three require more specialized training, Bluestine said. She encourages law and journalism students to volunteer because they have the training to take on more responsibility.

No matter what stage students are working on, though, they’re guaranteed to learn a lot about the process of the U.S. criminal justice system and how people are mistreated within it.

“Every time I hear an inmate’s story it’s usually a case of bad lawyering,” Taj said. “How many times the same person can be let down is very upsetting.”

Rudman described a trip to a prison in Graterford, Pa., where the class spoke to inmates who claimed they were innocent. He was surprised that the inmates whose stories were more believable were less vocal about their innocence.

“They don’t talk about it,” he said. “People shut down when they’re getting blocked at every step for 20 years.”

Morgan Ashenfelter can be reached at morgan.a@temple.edu.

Hi, my name is Lori Collins and I desperately need your services. My brother is currently serving time and was scheduled for release this April, after serving 12 years. Now, all of a sudden, he is being charged with a murder that took place in 1993. These charges were brought on my the allegations of another convicted felon. My brother is innocent and had nothing to do with that crime and we have no money to prove that. There is no evidence, whatsoever, against my brother! Please help me! 708 574-9965 I need your guidance and assistance more than anything!