With the recent movie release of Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic, the Rosenbach Museum explores the beginnings of a phenomenon.

They get increasingly angrier.”

That’s how Patrick Rodgers, the Traveling Exhibitions Coordinator of Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum & Library, describes each of Maurice Sendak’s 44 drafts of Where the Wild Things Are. Even diehard fans may not know this many drafts of the 10-sentence manuscript exist.

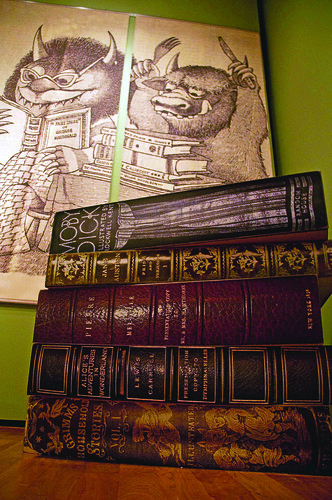

Advertised as an exhibition that will show visitors why the book is still popular nearly 50 years after its publication, the Rosenbach’s exhibition “And It’s Still Hot: Where the Wild Things Are” fails to do exactly that. Still, fans will find plenty of good reasons to visit the one-room showcase, which runs through Oct. 25.

The exhibition warrants one immediate response – awe. Sendak’s artwork, especially the nine final drawings on display (done in pen, ink and watercolor), is immeasurably powerful in person. The colors are stronger and more suggestive in person than they could ever be in print.

Other items on display are a dummy book (a second is on display downstairs in “Too Many Thoughts to Chew: A Sendak Stew”), four of Sendak’s 44 drafts, one book in Turkish, two posters, one libretti from the opera of Higglety, Pigglety, Pop!, Where the Wild Things Are and various other items bearing images of Sendak’s Wild Things.

Upon closer inspection of these items, the creative process that led to Sendak’s Caldecott medal-winning manuscript stands out. Any amateur artist with experience shading on the reverse of an image to simplify its transfer will appreciate the knowledge that even professional artists like Sendak are not above using such a shortcut.

Another striking image is in one of the preliminary sketches on display, a little girl appears. Fans of Where the Wild Things Are know there is no other human character in the book other than Max. Sendak appears to, at times, severely edit his drawings as well as his words.

Visitors may wonder how many drawings Sendak did before he settled on the final images if it took him 44 drafts to get the text just the way he wanted.

“Strangely, [Sendak completed] only two or three drawings before the final version,” Rodgers said. “He began writing drafts of Where the Wild Horses Are in mid-April of 1963 and by the end of April, it was Where the Wild Things Are. He was trying to get it done by August.”

The project ultimately took just six months to complete compared to the six years Sendak took to write Outside Over There, a book Rodgers said is often grouped with Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen because the books all represent his childhood in some way.

Although it took Sendak six months to write the manuscript, it took nearly 18 years to complete the live-action movie based on the book. Where the Wild Things Are, directed by Spike Jonze, opened in theaters on Oct. 16.

Rodgers said the reason he thought the movie took so many years to complete was that Sendak hadn’t found the right artist to bring Max and the Wild Things to the big screen.

To Rodgers, the Wild Things has inspired spin-offs like the Rosenbach exhibition, Dave Eggers’s novelization entitled Wild Things and a major motion picture “[because] I think kids still find it interesting. It’s kind of mysterious.”

“The focus is on Max and his emotions, and you get the feeling that these monsters come and go as they please,” Rodgers said. “[Sendak] was making an allegory about childhood.”

Rosella Eleanor LaFevre can be reached at rosella.lafevre@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment