A Michigan State study finds college students don’t perform well in science.

A recent study conducted by Michigan State University researchers, which surveyed 525 college students at 13 institutions across the country, found a majority had low levels of scientific literacy.

Their low level of scientific literacy means they did not use scientific, or “principle-based,” reasoning, to explain phenomena they know are true but don’t fully understand.

When asked about weight loss, many students were not able to scientifically account for the lost matter other than saying it had, “burned off” or “melted away.”

The conclusion drawn is that the majority of college students lack knowledge of key scientific concepts. Many students possess misconceptions based on outdated information or ideas from movies and pop culture.

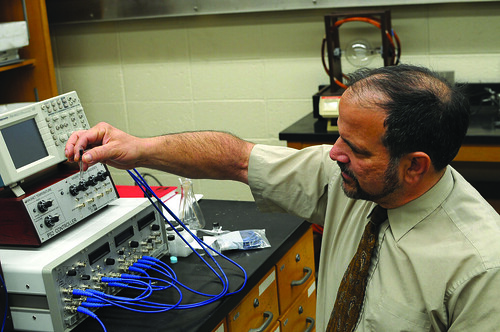

Professor Dr. Jonathan Nyquist has battled these misconceptions for years. Nyquist said as a general education instructor, many students are “science phobic” or have misconceptions about science in the real world.

“Certainly, everyone has misconceptions,” Nyquist said, adding sometimes old knowledge is overturned in favor of new ideas so that ideas one could have learned in school become obsolete.

In his class, Disasters: Geology vs. Hollywood, Nyquist shows clips from Hollywood movies, and asks his class if the scenario is possible. Nyquist said what students see in these movies and in other pop culture can become assimilated into their worldviews and can be difficult to correct.

“The borderline between science and fiction is very much blurred,” Nyquist said.

When five science majors and five non-science majors were asked if they knew and could state the laws of conservation of matter and energy, five out of five science majors could answer, while only two out of the five non-science majors were able to.

“I don’t think I’ve heard of that stuff since high school,” Craig Myers, a sophomore English major, said.

Low-scientific literacy is a problem, and the authors of the MSU study noted they chose this area of scientific knowledge to test, “because an understanding of these processes is essential for scientific literacy and good citizenship practices.”

“They hear things from both sides, and they need to know enough to be able to understand and assess the arguments,” Nyquist said.

Nyquist said he wants his students to do more than memorize information for a test; he wants them to “carry it on 10 years later, when their kids start asking questions.”

Michael Polinsky can be reached at michael.polinsky@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment