Content warning: This story contains mentions of eating disorders, which some readers may find uncomfortable.

Temple University’s Wellness Resource Center sponsored a virtual art show on Feb. 22 showcasing work from individuals who received treatment for eating disorders at the Renfrew Center of Philadelphia to commemorate National Eating Disorders Awareness Week.

About 30 students and staff members attended, said Janie Egan, the mental well-being program coordinator at the Wellness Resource Center.

Sondra Rosenberg, director of art therapy at the Renfrew Center of Philadelphia, presented the artwork and explained the thematic links between the pieces and the artists’ eating disorders.

“Art therapy gives them a way to access and express a lot of different underlying issues, thoughts and feelings that may be hard to get at using words alone,” Rosenberg said.

Eating disorders are serious illnesses associated with disruptions in eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions and can be associated with a person’s focus on food, body weight and shape, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

The Wellness Resource Center partnered with the Renfrew Center, a national network of eating disorder clinics, for the event to give a voice to people with eating disorders and “normalize getting help,” Egan said.

At the event, Rosenberg sorted the pieces by conceptual themes and explained how the artwork represented the emotional journey the artists went through during recovery.

One common theme across the artwork was “absent, covered and exaggerated mouths,” which explored the artists’ fixations on mouths as a weapon against themselves, representing the desire to keep food out and words in, Rosenberg said.

Another theme was “prisons and cages,” an expression of the artists’ feeling of being trapped by either their disorder or their doctors, Rosenberg said.

Jamie “OJ” Bushell, a former Renfrew Center patient who was treated at both the Philadelphia and Boston, Massachusetts, locations, underwent several different types of treatment, including inpatient and intensive outpatient treatment, for their eating disorder during a six-year span, Bushell wrote in an email to the Temple News.

During their recovery, art helped them to “give voice, formulate and conceptualize” the parts of themselves they could not express through words, Bushell wrote.

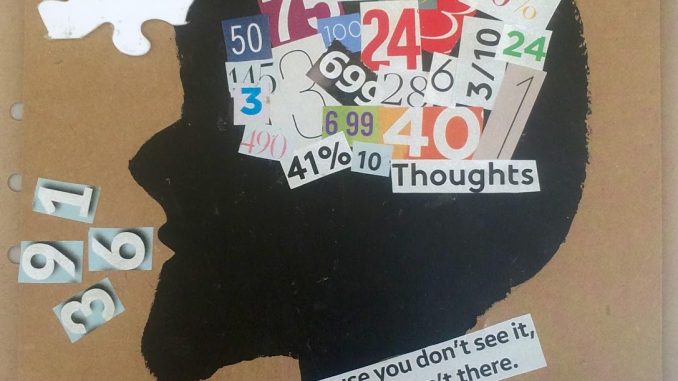

One of Bushell’s pieces depicted a black silhouetted head filled with numbers overlaid with a panel of red bars and the words “numbers are imprisoning” written at the top.

The numbers symbolize how many miles Bushell ran, how many calories they burned and how many bites of food they took, among other things. The combination of numbers and bars represent how the fixation on numbers harmed Bushell, they wrote.

“Layers are always something I liked to play with in art therapy because they feel so symbolic of my experiences as a whole,” Bushell wrote.

Another theme presented was “holes, voids and spirals,” which included illustrations of large holes and spirals often at the stomach or core of the piece. These images represented what patients often referred to as an emotional void, Rosenberg said.

The final themes presented were “trees and blossoming” and “finding your voice,” both of which represented the hopeful future of recovery from eating disorders.

By creating art, the artists were able to process their own struggles with perfectionism and self-criticism and connect with other people through sharing their artwork, Rosenberg said.

“Art can not only let you express yourself in ways you might not have been able to with verbal language, but it also may help others in your support team better understand your experience,” Bushell wrote.

Be the first to comment