During 2007 in San Diego, California, the thought of talking to people pursuing reparative therapy—or the attempt to eliminate homosexuality through therapy and ministry—seemed “bizarre” and a little insane to associate professor of sociology Tom Waidzunas.

“It didn’t seem like a reasonable project,” Waidzunas said of his proposed dissertation to address how scientists measure and conceptualize sexuality through the lens of reparative, or ex-gay, therapies.

At the time, Waidzunas was a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego, inspired by discussions about the pursuit in the early 2000s to measure race which caused scientists to create “racial divisions rather than, in some sense, discovering them,” he said. Waidzunas had seen similar work done within the confines of gender, but never with sexuality.

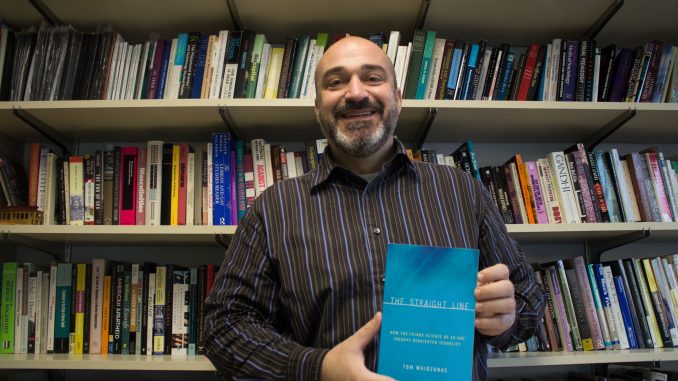

The dissertation that would eventually become the full-length work “The Straight Line: How the Fringe Science of Ex-Gay Therapy Reorientated Sexuality” was born. The research behind “The Straight Line,” published in November 2015, put Waidzunas in the middle of a fierce debate on ex-gay therapies in the United States and beyond.

“It was quite a time to follow this story,” Waidzunas said. “At first it was nonexistent, and then it was everywhere.”

In 2009, the American Psychological Association released a report condemning conversion therapies. In 2012, Robert Spitzer, a widely-respected psychiatrist, apologized for his 2003 investigation that ultimately supported the idea homosexuality could be “cured.” In 2015, only a few months before the book was released, President Barack Obama joined the movement against conversion therapies.

“It became an incredibly news-central topic while I was researching it,” Waidzunas said. “Now that the book is out, it’s kind of faded away.”

“But these conversion therapies are not completely gone,” he added. “They’re just going underground. The Texas Republican Party still maintains a pro-conversion therapy stance in its platform and the state of Oklahoma has a ‘right to reparative therapy’ bill.”

“The Straight Line” is also still relevant, Waidzunas added, because Western ideals of rights and our categorization of people is not the only way of thinking.

“So I think it’s an important read … for understanding global flows of knowledge and conflict,” he said.

“This is different than anything else,” said Julia Ericksen, the retired professor emeritus of the sociology department. “It’s a fantastic project. No one has thought before to write about this movement.”

Ericksen, who volunteered to help Waidzunas turn his dissertation into a book upon his arrival at Temple in 2012, said “The Straight Line” was unconventional in the field due to Waidzunas’ expertise in science. The topic of conversion therapies is interesting, she said, but Ericksen particularly enjoys the way the book shows “how science is used and the way it’s used.”

“We think of science as this objective thing,” Ericksen said. “Nothing controversial. It’s correct. But science is political like anything else.”

Though Waidzunas was first interested in the topic due to his fascination of how scientists conceptualize sexual orientation, he said, there was an element of personal interest as well. Waidzunas came out as gay at age 19. As a Texas native, he saw—though was not a part of—ex-gay ministries and its effects.

He’s personally grappled with the issue of sexuality and how it becomes a political position for many people, who sometimes don’t realize it’s not simply a debate for everyone involved.

“People’s lives become a battlefield,” Waidzunas said. “That’s not just gay people. That’s women’s lives, too.”

Waidzunas wanted to create a historical chronicle of the evidence for both sides, pro-gay and ex-gay. By documenting the scientific research on both sides, Waidzunas wanted readers to understand the claims made in order to move forward and “create a more human world around sexuality.”

What both pro-gay and anti-gay share—and what Waidzunas challenges in “The Straight Line”—is the idea of gay essentialism, or the theory that an underlying nature dictates an individual’s sexuality. In the book, Waidzunas adopted a queer theory perspective, which rejects the idea that people are born with an existing sexuality.

He hopes “The Straight Line” can promote discussions about sexuality “without appealing to nature or some absolute morality.” Appealing to a purely natural basis of sexuality, Waidzunas warned, can lead to ideas of a “gay gene” that might mean genetic screening and other challenges to gay rights.

“There’s no guarantee of gay rights just because we hold up flags that say, ‘Born this way,’” he added.

Victoria Mier can be reached at victoria.mier@temple.edu

Be the first to comment