International students talk about their first experiences with Valentine’s Day.

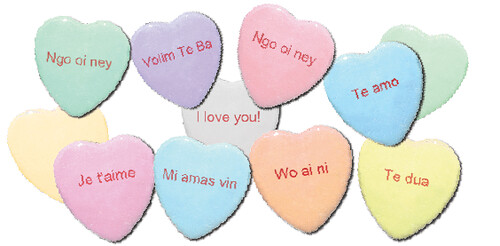

Love may be an international language, but what Valentine’s Day represents is in the eyes of the beholder.

Main Campus has a large international student population – approximately 715 students to be exact. Some of those students come from cultures that simply don’t celebrate Valentine’s Day, or have a different take on it than American culture. To help U.S. natives understand what that’s like, several international students explained what they make of all the chocolates, roses and armed naked babies.

“This is my first semester here at Temple and in the United States,” Abdulraxma Bajabaa, a freshman electrical engineering major from Saudi Arabia, said. “Here, you have so much more freedom. I mean to just go hang out with your girlfriend or something like that – you just can’t do that in front of everyone in Saudi Arabia.”

“Unlike in the United States, we are very private,” he added. “It is not a religious thing. It’s just how the culture is.”

Having only been in the U.S. for a few months, Bajabaa said he is still taking it all in.

“We don’t celebrate Valentine’s Day where I am from,” he said. “This is my first time here in America, and I haven’t had the chance to experience that holiday just yet.”

Although Bajabaa isn’t in a relationship and doesn’t have any special plans for today, Feb. 14, he said he’s confident that he will still be keeping himself busy.

“I’ll probably just be going out with my friends or something,” he said. “And the girls here are just amazing. It’s just like, wow.”

Soukaina Carakat, a junior mechanical engineering major originally from Morocco, also has little experience with Valentine’s Day.

“I’ve been in the United States for two years now, but I have no idea how people here celebrate it,” Carakat said. “But from movies, I can tell it is pretty different.”

“They just began celebrating Valentine’s Day [in Morocco], actually,” she added. “People from different countries started to go there. It was never celebrated before, because of religion, but in the last five years or so they have been celebrating it.”

Newly adopted in Morocco, Cupid’s holiday is still only celebrated predominately by people who are married rather than unwed couples.

“I don’t know what they do here in the United States, but couples go out and do not spend the night together,” Carakat said. “Maybe they just go out to dinner. Married people do celebrate it more, though, because of the religious reasons.”

Carakat isn’t currently in a relationship and said she has plans to spend the day with some good friends.

“I’m going to New York. Two of my friends there are single too, so we are going to celebrate together,” she said. “So it’s going to be like a friends Valentine’s Day.”

Saphir Esmail, a freshman international business major from Kinshasa, in the Dominican Republic of Congo, is planning on entertaining a member of the opposite sex this upcoming Feb. 14. He stressed that the holiday should not be taken too seriously, though.

“I’ll take this girl out for dinner and spend some time with her,” Esmail said. “I guess if you take the pressure out of the holiday, it’s actually a really fun day. It’s a good day to get to know someone better.”

Esmail said he thinks that Americans put too much emphasis on getting a date on Valentine’s Day.

“Here, it’s like a big thing, I guess,” he said. “There’s this pressure to have a Valentine on Valentine’s Day. It’s a really structured holiday that you feel obligated to celebrate. It’s a lot bigger here than back at home.”

In Kinshasa, where Esmail is originally from, locals celebrate Valentine’s Day. However, Esmail was quick to point out that it is much more low-key than in the U.S.

“Where I’m from, if you don’t have a Valentine it’s really no big deal,” Esmail said. “I guess it just depends on who wants a Valentine and who doesn’t. It’s not really a big thing like it is here.”

He said he believes that the emphasis placed on Valentine’s Day by those marketing holiday products put additional – and unnecessary – pressure on everyone.

“It’s, like, very marketed,” Esmail said. “If you go to the store, you’ll see that a lot of products are oriented on Valentine’s Day. Back at home, we don’t really focus on Valentine’s Day at all. If you want to celebrate it, you celebrate it.”

“If you want to take part in it, you take part in it,” Esmail added. “They don’t really market it as much.”

Millie Gateka, a 2010 international business alumna and native of Ethiopia, said she feels similarly about Valentine’s Day.

“It’s different here in America,” Gateka said. “As with most things American, it’s very commercialized. Not that I believe it to be a good or bad thing, it’s just how it is.”

Gateka is of the opinion that this commercialized holiday creates undue societal pressures.

“It just bothers me a little how people become like, ‘Oh my God, nobody loves me,’ all because they did not have a Valentine that year,” Gateka said.

When asked whether people in her homeland of Ethiopia celebrated Valentine’s Day, she confirmed that they did, but differently than in the U.S.

“The traditions there were kind of similar, but were still different.” Gateka said. “When I was younger, we sold roses and exchanged cards, but it was never that big of a deal to me, personally.”

“I’m not anti-Valentine’s Day,” Gateka added. “I can’t be against celebrating love.”

Hiren Patel, a senior marketing major from Ahmadabad, India, said he isn’t against celebrating love, either.

“I’ve been in a relationship for about nine months now, and on Valentine’s Day weekend I’m going to travel over to Boston so that I can spend some time with my girlfriend,” Patel said. “I’m pretty excited about the situation and about seeing her.”

Patel views the upcoming holiday as an opportunity and an excuse.

“It definitely a good thing for me because, [with] her being in Boston and me living here on Temple’s campus in Philadelphia, it can be tough for us to spend time together,” Patel said. “This way, we feel kind of obligated to do something that we want to do anyway, but don’t always have the time to do.”

Patel is unfazed by the barrage of in-your-face advertising that accompanies Valentine’s Day in this modern age.

“It is what it is,” he said. “That’s just something that I like to do for her. I mean, do you expect stores not to do that? I don’t really think it’s a big problem, I’d be getting her something nice anyway.”

Patel said that for the most part, Indians do not celebrate Valentine’s Day.

“Valentine’s Day in India does not necessarily exist,” Patel said. “The culture is built primarily on family values, so even smaller public displays of affection are looked down upon. In the country of India, the intimacy culture is very shy and private.”

Roshan Choithram, a junior finance major, who was raised in Indonesia but is of Indian roots, said he believes that the westernization of his home country is a good thing.

“I think it’s a positive thing, it’s going in the right direction,” Choithram said. “You know, globalization. It is going to happen sooner or later, either way.”

According to Choithram, Valentine’s Day is one example of that westernization.

“Valentine’s is getting really crazy there and it’s getting crazier and crazier as time progresses, Choithram said. “When you go to the store, it is heavily marketed to you. There [are] signs telling you to get this or get that, get roses. It’s getting bigger, it’s getting more westernized.”

For Choithram, Valentine’s Day in the United States is the same as in Indonesia.

“You bring roses to the girl. Take her out to dinner, the movies, maybe drive around a bit and then go home,” he said. “No special twists.”

When asked if he had any special plans for the day, he jokingly said, “I’m single and ready to mingle, but I’ve got about four papers due around that day.”

Adopting a more serious demeanor, Choithram spoke on what Valentine’s Day really means to him.

“It’s basically a day to show that you value your girlfriend, your sister, your mother,” he said. “According to me, it is not specific to your girl. It’s more about showing love to people who really mean a lot to you.”

John Dailey can be reached at john.dailey@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment