The night I found out my father had cancer, my mom did most of the talking.

She counsels hospice patients for a living, so when she sat my older sister Kayla and I down on our parents’ bed one night four years ago, I wasn’t looking at my mother — I was looking at Joyce Baker, the social worker.

She admitted that my father’s overnight hospital stay that week was not due to pancreatitis, as she had previously told us. The doctors had found a mass: non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“If you’re going to have cancer, this is what you’d want to have,” she continued.

It’s treatable. Most cases aren’t even terminal. Kayla and I turned toward my father to see if he shared this outlook, but he had his back to us, watching football on the TV in the corner. He looked over his shoulder to give a small smile. We weren’t convinced.

I felt numb as I went to brush my teeth, searching my eyes in the mirror for a hint of a tear. I was about to step into my bedroom when my mom stopped me.

“It’s OK to let it out,” she said, and that was enough to open the floodgates. To this day, I wonder if my dad could hear me as I sobbed on my mom’s shoulder, the light from the TV flickering through the hallway.

It wasn’t a surprise to me that the man at the center of it all chose to sit on the sidelines. He struggles to connect with my sisters and me, and he seems to think that the few interactions that bonded us to him when we were toddlers — ruffling our hair and calling us names like “Butterbean” and “Poogie” — are enough now. There’s love there, but there’s a wall, too.

In the few years prior to his diagnosis, my mom had lost her mother, father and sister to their own battles with cancer. During the aftermath of each, when the rest of us were comforting one another, he was out back repairing the lawn mower.

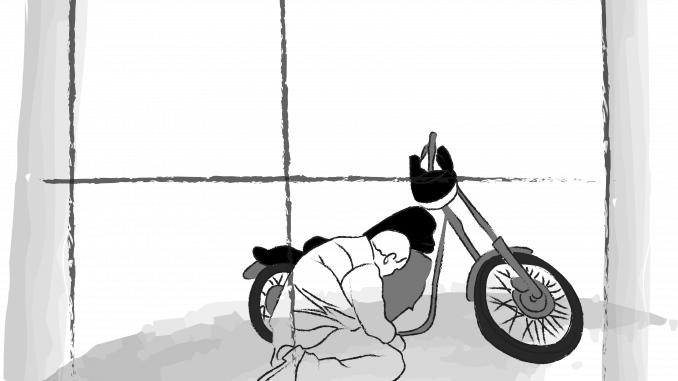

My dad continued to work on little, productive tasks like this throughout his chemotherapy. On his bad days, he’d sit in bed on the computer, scrolling through eBay for transmissions and exhaust pipes. On his good days, he’d roll out his Harley and spend hours in the yard dismantling its framework. I assumed this was his way of playing handyman with his emotions — hammering away the fear.

Little did I know, these projects were something more. “They were long-term things,” he told me much later. “Something to keep me alive for another year. That way, I didn’t have a choice. I had to finish.”

It was reassuring to see him tinkering away, as always. From Kayla’s and my perspective, things didn’t seem too bad. Our visits to the hospital were infrequent, at his insistence.

He claimed it was so we could focus on schoolwork, but I think he didn’t want us to see the version of him that paled under fluorescent lights and shrunk inside of a shapeless, floss-green gown. When we did stop by, all of us tried to keep up family dinner conversation. I’d offer him a bite of the chocolate cake I grabbed from the cafeteria and frown when he said no, because refusing food was so unlike him. Still, he could sit up in bed. He could joke without having to catch his breath.

As it turns out, times like these were rare. It wasn’t until two years later that my mother told me about the moment when she thought my dad might not make it. She decided to take a slice of pizza from a party she attended to my father in the hospital. Less than an hour into her visit, he got violently ill. His heartbeat climbed, his fever rose to 104 degrees, and he lost control of his bowels. As my mom looked on, she recalled with horror the hospital’s rule against feeding patients food that’s reached room temperature.

My sisters and I were sheltered from all this.

There were hints of his struggle, though, the biggest of which were the tears. Prior to his diagnosis, I had only seen my dad cry once, maybe twice. But when he departed on his overnight hospital stays, he would put on his coat and grab his bag, looking like he was off on a business trip, until he turned to me with tears in his eyes. Soon enough, I grew accustomed to feeling him shake as he hugged me goodbye.

The news that the tumor had finally disappeared was delivered tentatively. My mom was sure to tell us that it could always come back. Now, more than four years later, I’m afraid that I haven’t learned the lessons one’s supposed to from near-death experiences.

When my dad and I are alone in the kitchen together, I look at my phone instead of asking about his day. I forget to appreciate the fact that he’s here to ask why I don’t want to go to law school or to wake me up on Sunday mornings as he fires up the power tools outside.

But every time I hug him before returning to school, he wells up. In those moments, I know he hasn’t forgotten a thing.

Brianna Baker can be reached at brianna.nicole.baker@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment