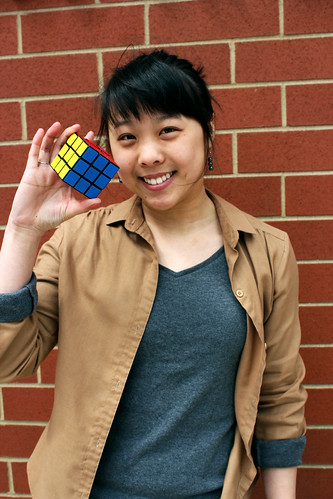

For many people, solving a Rubik’s Cube can be an all-day affair. For first year medical student Stephanie Chow, it takes just 16.9 seconds.

In high school, Chow, a California-native, was introduced to speedcubing, which is solving a Rubik’s Cube or related puzzle as quickly as possible. At the time, she was unaware that she would soon earn a spot among the top speedcubers in the world.

“My friend in high school was the former world record holder for speed cubing,” Chow said. “He gave me a Rubik’s Cube for Christmas in 2006, which was the start of it all.”

What arose as a hobby quickly became much more than just that. Chow found a place to flourish in speedcubing while attending the University of California at Berkeley.

“We had a really big Rubik’s Cube community there,” she said. “We had a lot of good people who could teach others. Everyone wanted each other to get faster, which helped me. It was really a great breeding ground for us to cultivate the skill.”

Chow quickly developed the skill and dove into the fierce competition circuit both inside and out of the World Cube Association. Berkeley’s speedcubing club typically hosted four competitions annually and traveled to various competitions across the country to compete. Chow also competed in U.S. national competitions in Cambridge, Mass., Atlanta and Stanford, Ca.

“The first time [speedcubing] was the worst. My hands got sweaty [and] the cube became difficult to turn, but you get over it with practice,” Chow said.

Within four years of picking up a Rubik’s Cube, Chow became the female world record holder for the Square-1 puzzle, a variation of the Rubik’s Cube. At the Reno/Lake Tahoe Winter 2010 Cube Competition, Chow took first place in the Square-1 and the Pyraminx events. Since 2003, the winner of a competition is determined by taking the average time of the middle three of five attempts at the puzzle.

“I think I’m like third or fourth in the world now, but I have not been to any competitions lately,” Chow said.

At Berkeley, Chow taught two classes on how to solve the Rubik’s Cube. Upon completing her undergraduate degree at Berkeley, Chow transitorily took a sabbatical from competitive speedcubing.

“The main reason why I cannot compete is due to time restrictions with school, but I have had classmates approach me wanting to learn, so I teach them on the side, individually,” Chow said.

While Chow has helped others prosper into better speedcubers, speedcubing, in turn, has aided Chow’s studies.

“It helps me a lot in embryology and neuroscience,” she said. “I would like to think it gives me a good 3-D perception. Being able to map the 3-D structure of the brain and where all the nuclei are is useful.”

It is widely reported that the creator of the Rubik’s Cube, Hunagrian architect Ernő Rubik, created the Cube as a teaching tool to help his students understand 3-D objects. He did not realize that he had created a puzzle until the first time he scrambled his new Cube and then tried to restore it.

Joseph Schaefer can be reached at josephschaefer@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment