Jerome Harris grew up reading his mother and grandmother’s copies of Ebony and Jet magazines without knowing the art director of the magazines’ publishing company, Leroy Winbush, was a person of color.

He then taught himself graphic design by creating party flyers that reflected the work of Black designers he knew from the magazines.

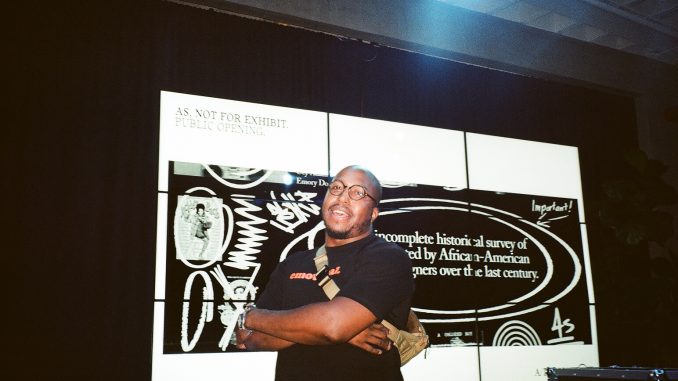

Harris, a 2008 advertising alumnus, created “As not for: Dethroning our Absolutes,” a project curating artwork of 15 Black designers from the 1870s to 1999. The project is exhibiting in different institutions across the country and is currently at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and Hennepin Theatre Trust in Minneapolis, Minnesota until Nov. 10.

Harris said that the exhibit, which started in 2017, is in its final stages, and he is planning to write a book bout it to close the project.

Harris curated the 47 artworks, featuring designers like Reginald Gammon, Art Sims, Grafton Tyler Brown, Buddy Esquire and W.E.B. DuBois.

Esquire, a pioneer in hip-hop party flyers of the ‘70s and ‘80s, fascinated Harris because he too, creates party flyers, he said.

“[They were] promoting these parties for hip-hop culture even before it had a name,” he said. “They were the voice of communications for these parties, and now it’s a worldwide culture.”

While starting on his MFA at the Yale School of Art, Harris researched Esquire, but did not find a lot of information about him, he said. He then expanded the art exhibit to include Black designers from the 20th century while he was a fellow at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Harris concentrated in art direction as an advertising student at Temple because of its focus on graphic design, allowing his designs to evolve over time, he said.

“The research … allows me to say, ‘Hey, I was making these design decisions because I was looking at this,’ or ‘I wanna pay homage to this designer,’” he added. “I can make a case for when someone says this is a bad design. I can say, ‘No, it’s not, let me tell you why it isn’t.’”

Dana Saewitz, chair of the advertising and public relations department, said Harris was an outstanding and creative student and is happy about his success with the exhibit.

“He’s just really an influential thinker,” she said. “This is a hugely underserved population of artists that deserve attention, and he has brought their work to the forefront, and I think that is really impressive, admirable and powerful.”

Dora Godfrey, Harris’ former colleague and friend from Yale, said that more research should be done in highlighting the works of Black artists and that Harris took a big step in that process. She is excited that people are interested in and interacting with the works at exhibitions, she added.

“He is genuinely interested in people’s stories, and I think that’s reflected in a lot of his recent work,” Godfrey said. “He has a lot of empathy, and I think that’s an important thing to have today.”

Harris said he hopes the project helps people learn and research more on design history, which he thinks shapes modern art.

“History is skewed in general toward white history, so I guess this is trying to even out the plane a little bit, just in my field,” he added. “There was a void in design history and education, and I don’t think anybody realized. I was like. ‘People should know about this,’ and I think it’s cool that people are taking a liking to it.”

Be the first to comment