In the most recent jobs report issued by the Bureau of Labor Statistics before the 2012 presidential election, the unemployment rate inched up, from 7.8 to 7.9 percent. In 2010 and 2011, the National Center for Education Statistics reported that the average price for a four-year institution of higher education cost a student $22,092, a more than $9,000 increase from a decade earlier when adjusted for inflation.

Still, another study by Rutgers University’s John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development in 2011 showed that 62 percent of college graduates working a job that did not require an undergraduate degree said they would need more education to further their careers.

In the midst of a shrinking economy and rising costs of education, the ability of all students to further their education through internships has been the subject of numerous reports, which aim to discover how students can become disadvantaged in a smaller job market.

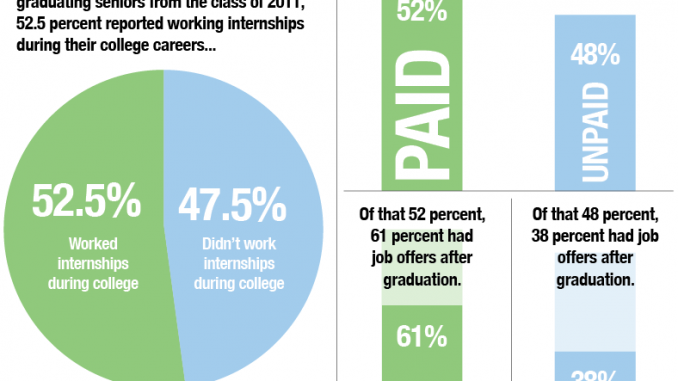

According to a National Association of Colleges and Employers survey of 20,000 graduating seniors from the class of 2011, 52.5 percent reported working internships during their college careers, of those, 52 percent were paid.

According to the survey, 61 percent of students working paid internships in the for-profit sector had job offers at the time of their graduation, compared to 38 percent of students who worked unpaid internships and one third of students who had no internship experience.

In addition, among the 50,000 total students surveyed, those who worked paid internships were more likely to spend their time working on professional tasks.

No government or private organization accurately tracks the exact number of paid and unpaid internships, although some studies have reported a rise in unpaid internships in recent years.

Under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, unpaid interns in the for-profit sector are individuals not considered employees by meeting six criteria outlined by the FLSA, according to the Department of Labor.

Under the FLSA criteria, an unpaid internship must be given for intern’s educational advantage where the employer does not benefit from the intern’s labor. The intern must not replace regular employees, and the intern is not necessarily guaranteed a job when the internship ends. The intern and the employer must also understand that the internship is not paid.

Between September 2011 and March 2012, the New York law firm Outten and Golden LLP, filed three class action lawsuits against the Hearst Corporation, Fox Searchlight Pictures and “Charlie Rose” on the behalf of separate clients who all worked as unpaid interns in accused violation of the FLSA standards.

Outten and Golden own a website titled unpaidinternslawsuit.com, where it advertises seeking potential clients who have worked as unpaid interns for Fox Searchlight, Hearst, or “Charlie Rose” to join their cases.

Elizabeth Wagoner, an employment attorney for Outten and Golden who has worked on the cases, said that corporations often defend their case by claiming that they are “training programs” – an exception that has been upheld by the Supreme Court. Wagoner said that while such exceptions have been upheld, if interns are performing work benefiting the company, legally they should be considered employees and paid as such.

On the website dedicated to the lawsuits, the firm states that the practice of unpaid internships “curtails opportunities for employment, fosters class divisions between those who can afford to work for no wage and those who cannot, and indirectly contributes to rising unemployment.”

“The only people who will be able to work these professions will be those who can afford to work for free,” Wagoner said.

According to a 2012 NACE survey of employers, those surveyed said they planned on increasing summer intern positions by an average of 8.5 percent, most of which would be paid.

At Resources for Human Development Inc., a Philadelphia based non-profit specializing in social services, Human Resource Director Roger Lenz helps oversee a paid internship program that hires students from nearby colleges and universities to work paid internships conducting research and shadowing employees in fields like political advocacy and children’s services.

During their internships, students are paid a $750 stipend per semester, mostly to pay for commuting costs, Lenz said.

“We wish it could be more, but that’s all we can afford,” Lenz said. “We would feel guilty if they didn’t make any money at all for this experience.”

Lenz said that while he has never hired unpaid interns, he believes students generally have a desire to work hard regardless of how they are paid, but some students may be disadvantaged by financial constraints.

“I think that if it was not a paid internship…it would maybe discriminate against people at lower socioeconomic levels,” Lenz said.

“We believe that there is kind of a two-way relationship here that advantages both sides, we do get their innovation and we get their energy and we get their youth which really helps us,” Lenz added. “At the same time, they’re getting valuable additions to their résumé that could give them a competitive edge when they are ready to go out into the workplace.”

Allison Berger, a senior psychology major, completed a paid internship through Disney, where she worked at a restaurant in the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World. Paid hourly for her work as a server, Berger also received lodging at the park, which was deducted from her paycheck.

“I started the internship not really knowing what I wanted to do with my life,” Berger said. “That kind of led me to where I am now, and I really like the service industry.”

While at Disney, Berger said, she was able to take a leadership class, and other students had the option of taking marketing classes in networking and résumé building for a small fee.

In addition, Berger said Disney offered team building exercises, volunteer opportunities and extensive training for the internship job, which she said later helped her career opportunities in subsequent restaurant jobs.

“I was hired just because I was trained in the Disney-way,” Berger said.

Berger said she received two premiums while working at Disney, and that the compensation affected her ability to work the internship.

“I probably wouldn’t have done it if it weren’t compensated because I wouldn’t have had a way to pay for my housing or pay for my food every week,” Berger said. “Definitely knowing in the back of my head that I was getting paid…on those bad days it was kind of easier to justify going into work.”

While sophomore entrepreneurship major Jason Gelman said he would have taken any internship to help gain real work experience, the internship he landed at Temple Apartments gave him a special company experience – so much so that he renamed the business. Gelman said he was hired to what was then called Temple Apartments this semester after competing for a marketing internship he saw posted on Craigslist.

Gelman and one other intern were put in charge of helping two landlords market and sell leases to houses they own in the streets around Temple. For their work, Gelman and his partner both received $700 commissions on the houses they leased.

In addition, Gelman and his partner set up a Facebook page for the company and developed a new title: Urban Life Management.

“They said we could control the entire aspect of the business, they own the the properties so they want someone to go out and market them and sell them,” Gelman said. “I really thought it would be beneficial because I’m an entrepreneurship major.”

“It’s all on us, we’re getting what we put into it,” Gelman said about the commissions. “[Being able to work a paid internship] gives you a different outlook, you’re working to the full extent and in the future…that would definitely make it easier going into a job knowing that I’ve been on a personal level with a company.”

For employers like Lenz, applicants for entry-level positions that have internship experience are at a definite advantage in the hiring process. Lenz also said the connections interns build with the company are a major factor that help them to later get hired over other applicants.

“The one thing that is very difficult to understand from someone’s history is how are they going to work not just in this job, but how are they going to do in our [company’s] culture, it’s a big intangible,” Lenz said.

John Moritz can be reached at john.moritz@temple.edu or on Twitter @JCMoritzTU.

Be the first to comment