In nine days he would be elected the 35th President of the United States. But on this Halloween afternoon he seemed like just plain Jack, a handsome 42-year-old Irishman with a Boston accent and a Coppertoned face, talking to a crowd of students about Richard Nixon, President Eisenhower and a nation in decline.

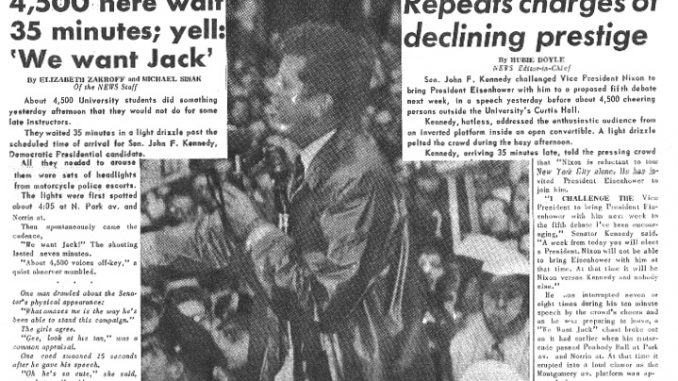

“We want Jack! We want Jack!” the crowd of 4,500 chanted as the open limousine carried John F. Kennedy south to the 1800 block of Park Avenue and stopped outside Williams Hall, then a women’s dormitory. Coeds ogled – there was no Google then – from their open room windows. A huge “WELCOME” banner hung. A handprinted sign declared “America Wants Kennedy.”

Standing on a platform inside the limousine and wearing a dark raincoat in a light drizzle, JFK first charmed the students with his sense of humor and history, and then gave them a blunt appraisal of Nixon.

“Bismarck,” he began, “once said that one-third of the students of German universities broke down from overwork, another third broke down from dissipation and the other third ruled Germany. I do not know which third of the student body is here today, but I am confident I am talking to the future rulers of America…”

Kennedy said he could not believe any educated person could accept Nixon’s campaign of “unequaled prosperity.” He cited the 1954 and 1958 recessions, a 30 percent housing decline, and “more unsold cars in three weeks than we ever had in our history.” Noting there was no economic growth in the previous nine months, he declared, “I don’t want that kind of prosperity.”

He also faulted Nixon for boasting that the United States’ prestige had never been higher. He cited State Department polls showing a shift in the balance of power to the Soviet Union, whose launch of Sputnik in 1957 had startled these same students when they were in high school. But his thought was interrupted by a long microphone held by the late KYW News reporter Jay Strassberg.

“He is either misinformed, uniformed or misleads … when his own information service in the State Department – will you get this out of my throat? Thank you.” The crowd laughed.

But that simple request underscored the age of innocence that the Classes of 1960, 1961, 1962 and 1963 shared – until Nov. 22, 1963. Americans were able to get up close and personal with their presidential candidates, even poke at them. There was trust and no need for barricades of security, or wands, or body searches. Only motorcycle patrols escorted JFK to Temple. In New York City he once requested no police protection but was turned down.

The Temple University News, as it was known then, had four staffers cover JFK’s campaign visit. Hubie Doyle, the editor-in-chief, wrote the main story; Elizabeth Zakroff and I wrote vignettes. Zohrab Kazanjian, fondly known as Zorro, a foreign student from Baghdad who never returned to Iraq, took a classic photo of Kennedy against the backdrop of hopeful students eager for change.

Instead of threading myself through the compacted crowd for a view in front of Kennedy, I walked through the ruins of two rowhouses being demolished that sat back to back from 13th Street to Park Avenue and was able to stand right behind him.

He saved the news of the day for the last part of his short speech.

“I am going to make an offer to Mr. Nixon,” Kennedy began. “I have been trying to get him to debate me for two weeks. … I read in today’s paper that Mr. Nixon is unwilling to take a ride through the City of New York to meet the voters. But he is going to take President Eisenhower with him.”

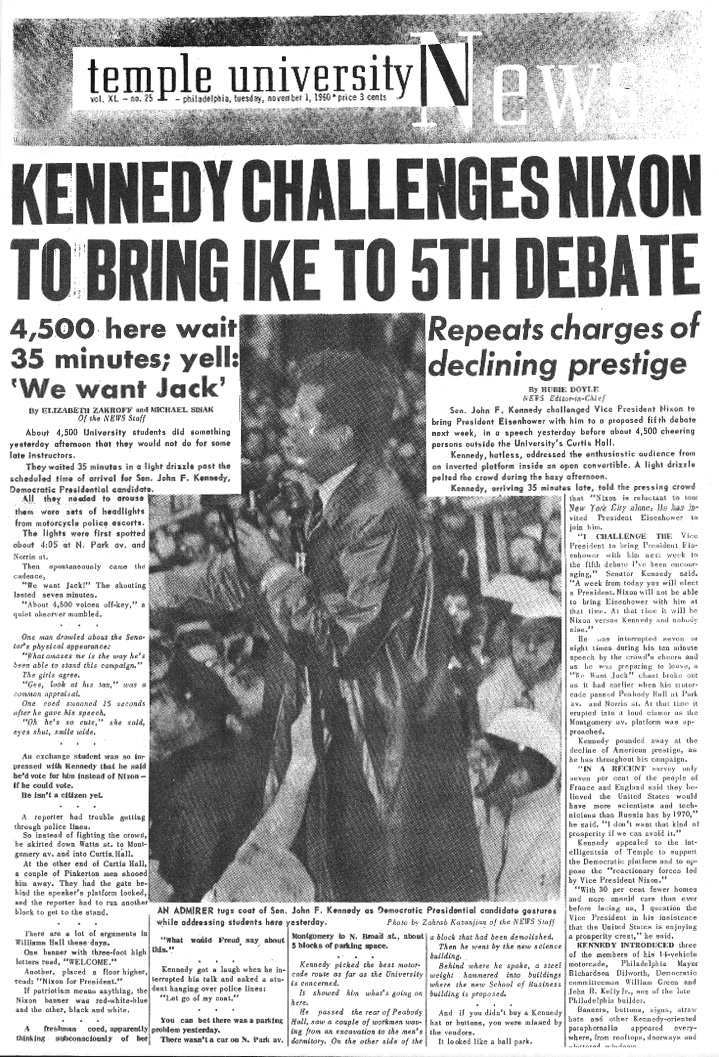

Kennedy buried the lead. “I now offer him to let President Eisenhower come with him on the fifth debate.” That brought a thunderous roar and applause, and fueled an international news story. “What Mr. Nixon does not understand is that President Eisenhower is not a candidate. Mr. Nixon is … no matter what the President of the United States may choose to do this week in New York or any place else. It is Nixon versus Kennedy, the Republicans versus the Democrats and I look to the future with some degree of hope.” The next day, Nov. 1, 1960, The News boldly headlined in inch-high type: “Kennedy Challenges Nixon to Bring Ike to 5th Debate.”

We all looked to the future with hope. We worked on election night compiling votes for NBC, a role that journalism dean J. Douglas Perry arranged. We nervously awoke on Nov. 9 to the surprise that Kennedy had narrowly won, by 118,000 of 69 million votes, thanks to the Philadelphia and Chicago landslides. We teared with joy while watching his inauguration on a black-and-white TV with rabbit ears, and we shared his inaugural address by house telephone (there were no iPhones then).

“Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

We worried about Cuban missiles being aimed at Conwell Hall. Renee Kassab, a Temple News reporter, assessed the role of the campus Civil Defense bomb shelters for Cold War challenges and assured us that we were all safe.

Then came that black Friday, Nov. 22, 1963. After a nightshift at the Philadelphia Bulletin, I was awakened in early afternoon to a radio chattering about an assassination attempt in Dallas. It did not make sense. I thought I was hearing another “War of the Worlds” spoof. But soon confirmation came that Kennedy had been shot and later that he died. At Broad and Norris streets, someone pasted on the huge journalism department windows bulletins from the wire-service Teletype machines. The campus went into a deep pall for a long time.

I drove in a daze to The Bulletin and found a newsroom working in funereal shock. It was so quiet that one could hear the TV set across the room. I was assigned a story about a group of suburban high school students who ironically were on a field trip to Arlington National Cemetery.

At Love Field a fateful decision had been made, according to PBS’s Jim Lehrer, then a reporter for the Dallas Times Herald. He was on a phone, dictating an update to his story about Kennedy’s arrival on Air Force One, when the rewriteman asked him if the Secret Service was putting the bubble on the limousine for the motorcade. Lehrer asked an agent, who confirmed that the rain had stopped in Dallas, and then that agent had the bubble disassembled. It was not bulletproof, Lehrer said, but it might have changed history.

Lehrer, whose new novel about JFK’s death is “Top Down,” was part of a distinguished reporting triumvirate that covered the assassination. Bob Schieffer was with the Dallas Morning News and Dan Rather was with the local CBS affiliate. A Bulletin colleague, John G. McCullough, stood with reporters near Jack Ruby when he assassinated Lee Harvey Oswald on live TV the following Sunday.

I continued a 50-year career, the last 30 as an editor at The New York Times. Hubie Doyle counted Fred Astaire as a friend and a public-relations client, and has written a memoir. Elizabeth Zakroff was a pioneer Vietnam War reporter for United Press International at age 23 and is now an attorney. And Zorro? He has taken more photographs of Temple people and events than anyone ever. His portrait of JFK will hang forever.

Michael Sisak, SMC ‘63, was editor-in-chief in the Fall of 1961. His seven-decade career took him from The Ambler Gazette to The Philadelphia Bulletin, The St. Petersburg Times, The Wilmington News Journal, The Los Angeles Times, Newsday, The Philadelphia Journal and The New York Times.

Be the first to comment