The Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent partially reopened after a three-year hiatus.

While Philadelphia’s story is nothing short of historic, the newly reopened Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent is putting a modern spin on how it is told.

“It’s very different from what you would have had in the old Atwater Kent, which was described by some people as a book on the wall and somewhat dry,” said Charles Croce, executive director of the Atwater Kent.

Previously, Croce has worked at the Kimmel Center and Philadelphia Museum of Art. He referenced the way the exhibits are written and displayed.

“This is much richer and written in first person – it’s a conversational tone, not pedagogical, not didactic or scholarly, but much more conversational,” Croce said. “It’s very different from the way most history museums present their text.”

The museum, housed in the original Franklin Institute building at 15 S. Seventh St., is historic itself, and was built in 1826. And it seems that every inch of the museum, rather than just the exhibits themselves, have some sort of legacy. The admissions desk in the front lobby was crafted from wood cladding taken from the Independence Hall clock tower, which dates back to 1820.

“The goal is really to get Philadelphians to kind of look at the city in a different way,” Croce said. “People say history is a bunch of old things, but history is being made every day. Look at Occupy [Philadelphia] – that’s making history – this city was built on protests, like with the Revolutionary War.”

“There’s more contemporary history being made every day,” Croce added.

The museum originally opened there in 1938, and closed in 2009 for what was intended to be minor upgrades. Three years and $5.8 million later, the building has received a top-to-bottom renovation, including new elevators, air conditioning, ventilation, security and other infrastructure improvements.

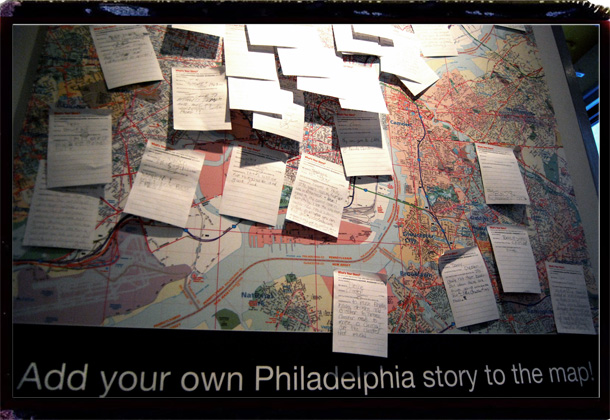

The Feb. 15 reopening includes two rooms of exhibits, and a third that houses a large floor map of the city, stretching from Ridley Park in the southwest and New Jersey in the southeast, to various sections of the northeast.

“It’s an appetizer, just a taste of what’s to come,” Croce said. “We’re viewing this as a new museum – not the old Atwater Kent museum reopening with different lights and paint. It’s a totally different concept.”

The first room houses “City Stories: An Introduction to Philadelphia.” The concise introduction covers 330 years in a modest, single room, with 40 objects on display. A “reader rail” describes important landmarks and significant moments throughout the city’s history. The artifacts and several paintings such as a portrait of Martha Washington, circa 1790, tell the story of Philadelphia’s immediate and not so recent past. A video with stories from Philadelphians discussing their own stories and what the city means to them plays on loop in the same room.

About 10,000 of the objects in the museum’s collection came from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and comprise much of what’s seen in this room. A more inventive aspect of the exhibit comes from a real-time “tag cloud.” Visitors can text a word to describe the city and its history, and the words grow on the screen based on how many participants have used them.

“Philadelphians have pride in their city, but don’t necessarily know its rich history,” Croce said. “Certainly they know the American Revolution – the three cornered hat, the liberty bell – but we’re talking about the history of manufacturing; I’m not sure people realize this city was considered the workshop to the world.”

The second front room, titled “Philadelphia Voices,” showcases artifacts from the city’s more recent history, such as boxing legend Joe Frazier’s boxing gloves, and acts as a “preview gallery,” outlining what is set to fill the rest of the museum once it is completely reopened.

Plans for a “Made in Philadelphia” exhibit reinforce the idea of Philadelphia as the “world’s workshop,” and its industrial history, producing textiles, clothing, beer, locomotives and many other objects. Another potential exhibit, dubbed “Played in Philadelphia,” will look at the longstanding tradition of Philadelphia sports teams.

Future exhibits will also invite the input of the general public to explore neighborhoods outside of those that are most frequently documented. One exhibit will intentionally focus on three intersections outside the common tourist hubs of Old City and Center City – Ninth Street and Washington Avenue, Eighth and Lehigh streets and Cecil B. Moore and Ridge avenues – where many of the more common historical destinations exist. The exhibit will examine how these intersections have changed during the years and look to the future of each, incorporating data such as the 2035 Plan – the city planning commission’s comprehensive outline of development in the city during the next 23 years.

In an aim to further incorporate everyday Philadelphians’ stories, visitors are invited to post their own stories on a wall map of the city, which was filled with notecards within the first few weeks of the building’s opening. This, and dialogues with community groups, nonprofits and other local organizations will form the basis of content for the future “Community Voices” exhibit. Stories are contributed either in the museum or on its blog.

Croce said that one of the most interesting stories so far came from a Roxbury woman, whose grandmother was an Irish immigrant who had worked as a cook in the estate of Atwater Kent – the man for whom the museum was named. More than 100 people have contributed stories so far.

“We found that people are very willing to talk about what they think should be included, we were pleasantly surprised at the reaction,” Croce said. “It’s the antithesis of how we describe Philadelphians – they may be opinionated, but want to share a great, underlying affection for a city they grew up in or their grandparents grew up in.”

With two galleries open and six left to fill until the museum will launch fully, Croce said that raising funds has become “the most important thing.” The remaining exhibits are planned to open by June, and Croce said that 634 visitors came to the museum in its first weeks.

He added that the museum is intended to give an overview of the city’s history, rather than focusing on one time period or area. Its Old City location, just blocks from Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, the National Museum of American Jewish History and other destinations, along with this broad format in which it is curated, makes it an ideal starting point for visitors to the city continuing on to other cultural and historical attractions.

“The idea is you come here, we present you with an overview, and guide you like a beacon into other areas of the city,” Croce said.

While the museum’s collection is “pretty rich” in 18th and 19th century collections, Croce said they are looking to add to and expand their collection from the 1950s and onward.

“It’s extremely important for this city to document its history, it’s like no other city in the U.S.,” Croce said. “Every other city naturally has a history, but this city is the quintessential study of the country’s history.”

Kara Savidge can be reached at kara.savidge@temple.edu.

Be the first to comment