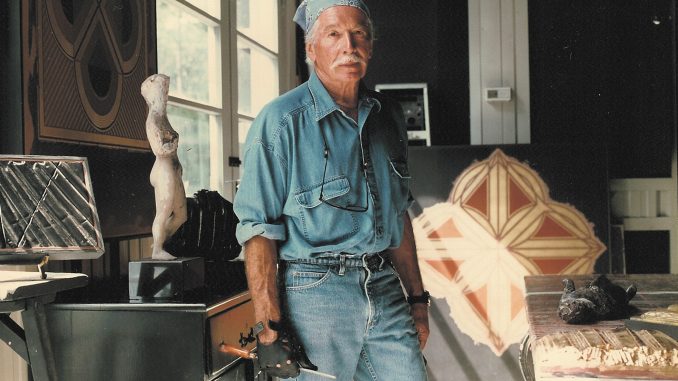

When creating art, George Dunbar occasionally uses a gun.

Dunbar, a 1951 painting alumnus, is presenting his first career retrospective, “George Dunbar: Elements of Chance,” at the New Orleans Museum of Art until Feb. 19. The exhibit will represent 12 artistic periods of Dunbar’s career.

Sometimes, Dunbar will load up a shotgun with birdshot and fire it at his clay and metal leaf artworks. Dunbar employs this technique, in addition to sandblasting and abrasive brushwork, to dull the shininess of the metal leaf and weather the clay.

Before the weathering process, Dunbar uses a centuries-old gilding technique to bind the metal leaf, using rabbit skin as an adhesive, to layers of colored clay.

“[It’s] the same type of technique that you see in gilded picture frames from the Renaissance and [Spanish] colonial pieces,” said Lizzie Shelby, one of Dunbar’s studio assistants. “But he has taken that further to distress these surfaces, so he [adds] things like layers of chopped-up pieces of fabric and chunks of wood under the surface of his work.”

“Elements of Chance” will feature some of Dunbar’s earliest paintings from the 1940s and 1950s, unlike “Dunbar: Mining the Surfaces,” his exhibit at NOMA in 1997.

These early artworks include action paintings, characterized by “the application of paint in free sweeping gestures,” according to the online art glossary of the Tate Museum, a public body aiming to increase understanding of British art.

Dunbar’s early action paintings were influenced by the abstract expressionists who achieved prominence during his years at Tyler, said Katie Pfohl, NOMA’s curator of modern and contemporary art.

“He chose Tyler because he heard it was a really progressive school that was open to a lot of the newest trends and art movements of the ’40s and ’50s, especially action painting by artists like Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning,” Pfohl said.

Dunbar said Tyler’s location also played a role in his artistic development.

“Being as close to New York as I was, I think that was a tremendous influence on what I liked and disliked in art,” he said.

Pfohl said she believes Dunbar has distinguished his work from his fellow contemporaries by applying a diverse variety of materials to modern art concepts.

“I think he viewed himself to be taking a lot of the ideas of artists in the New York school [of thought], the spontaneous gesture, and the belief in action and movement and capturing those in paint, and trying to bring those into terms that felt very indigenous to the local landscape in Louisiana,” Pfohl said.

While the various periods included in the exhibit are named mainly for the purpose of cataloging, Dunbar said some of the period names, like “Marshgrass,” one of the periods in which he used clay and metal leaf, evoke the textural elements of his art.

“The marsh…changes texture constantly every month,” Dunbar said. “So it most probably unconsciously has been an influence on my work.”

Pfohl said Dunbar continues to produce work in all of the previous periods. He still makes action paintings today, more than six decades after he began the series.

Dunbar co-founded the Orleans Gallery, the first contemporary art gallery in New Orleans, in 1956. Prior to the establishment of the gallery, New Orleans-based artists only had the option to sell their work in decorative stores, Dunbar said.

“We were able to [create] a very sterile, clean space, which really you didn’t have much of in those days,” he said.

Dunbar said he and his fellow artists at the Orleans Gallery were not attempting to represent the South, but rather considered their work on par with national and international trends.

“I’m not suggesting that the terrain and the colors here haven’t had some influence on my palette,” Dunbar said. “[But] I really think I’ve been more influenced by … artists such as de Kooning and people like that.”

Pfohl said Dunbar had a significant impact in exposing people in the South to new artistic ideas.

“[His art] has been embraced by a group of patrons and collectors and supporters and art writers,” she said. “Without his work, I think [they] would not have had that kind of exposure to abstract art.”

Ian Walker can be reached at ian.walker@temple.edu or on Twitter @ian_walker12.

Be the first to comment