While configuring a budget, Temple University must consider multiple factors. But perhaps the most important pieces to this puzzle is state funding.

Temple and the other state-related universities received a massive cut in state funding from the commonwealth in 2011 as a result of a lower amount of support for higher education and other financial struggles, said Ken Kaiser, the university’s chief financial officer and treasurer.

“There’s been a fundamental shift in the way the state has viewed supporting public education,” Kaiser said. “In the past, getting a college degree was viewed as everybody’s right. Now I think it’s viewed more as a privilege and the Commonwealth is saying, ‘That’s not really our responsibility to make sure that our citizens get a college degree. They can do plenty of other things without that.’”

In 2011, the state approved a 19 percent cut in higher education funding to Temple’s state allocation, from $172 million to $139 million. As a result of state funding cuts, Temple cut nearly $113 million out of its budget from 2009 to 2013, Kaiser said.

Eight years ago, state allocations made up nearly 65 percent of Temple’s budget. This year, state funding makes up only 10 percent of the budget, Kaiser said.

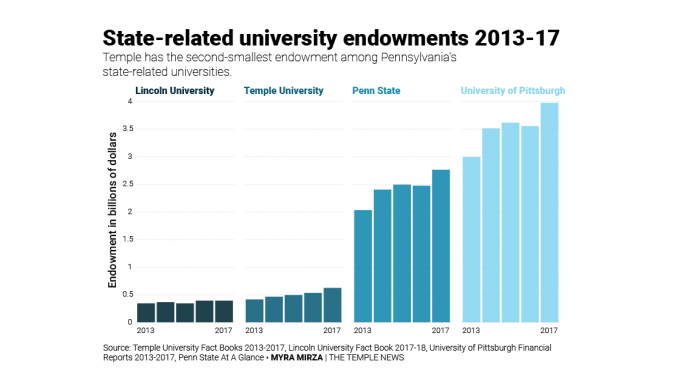

With a lower proportion of state funding, Temple hasn’t been able to freeze tuition since 2012, and it couldn’t this year — like Pennsylvania State University and the University of Pittsburgh could for some students — because it has a much smaller endowment than the other state-related schools.

In July, Temple received a $155.1 million appropriation from the state, which was about $4.5 million more than last year. The university’s allocation has slowly increased, but is still tens of millions of dollars away from what it once was. Other state-related universities like Penn State and Pitt also received a 3 percent boost in funds from the state.

TUITION INCREASES AND STUDENT DEBT

Despite this boost in funding, however, Temple increased in-state undergraduate tuition by 2 percent and 2.4 percent for graduate students in July. The state’s allocation pays for Temple’s in-state resident discount.

The additional $4.5 million from the state allowed the university to reduce the planned in-state tuition increase of 3.3 percent to 2 percent.

“The $4.5 million was, in effect, given back to students,” Kaiser said. “It directly reduced the amount in-state students were going to pay, and it should only provide a discount to in-state students because in-state residents are paying for it.”

With this increase, the new base rate for in-state tuition is $16,080, while out-of-state tuition is $28,176. Mandatory fees remained $890 per year.

“It’s hard to keep tuition increases zero when you’re losing a major funding source,” Kaiser said.

Universities in Pennsylvania and across the country typically increase tuition every year to keep up with the rise of inflation and labor costs, said Doug Webber, an economics professor.

“Costs for everything are going up, especially in higher education, and the single biggest cost driver is labor,” Webber said. “The incomes for people that have that much education in non-academic jobs are rising considerably, even faster than the rate of inflation.”

“A university is, in some respects, just like any other organization that has something that they are selling, and costs go up every year,” Kaiser said. “Just like at home, your utilities go up, and we also have to account for that.”

Webber said to keep professors working there, universities often have to raise their salaries every year.

As costs go up every year and universities increase tuition, students often bear the consequences.

Pennsylvania has the second-highest average student debt in the country, according to a September 2017 report from the Institute for College Access and Success. In 2016, 68 percent of Pennsylvania students graduated with loan debt, with an average debt of $35,759.

One of the primary reasons for student loan debt is the standard of living and a lack of state support in funding, Webber said. Large public and state-related universities like Temple, Penn State and Pitt are located in more expensive areas.

“There are a lot of public students in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh,” he said. “Therefore, the cost of operating in those cities is going to be much, much higher. You have to charge more tuition because you can’t pay professors and staff as if you are operating in a low cost-of-living area.”

COMPARING TEMPLE TO OTHER STATE SCHOOLS

Temple’s fiscal year 2017 endowment, which is an accumulation of gifts from benefactors, is $581.9 million — the highest it has ever been. But other state-related schools like Penn State’s system-wide endowment and Pitt’s are both $3.9 billion.

Temple receives approximately 4.5 percent of the endowment’s annual return, which is typically invested in areas like student scholarships. For every $1 million, Temple receives $45,000 as a return, Kaiser said.

“If Bill Gates loved Temple and said, ‘Here’s $20 billion for a scholarship endowment,’ our tuition would be basically zero,” Kaiser said.

Penn State and Pitt were able to freeze their in-state tuitions this year because of the state’s 3 percent boost and its large endowments, Kaiser said. Temple last froze its tuition in 2012.

“We simply don’t have the wealth and the resources that Pitt and Penn State have, and we’re unable to do the zero that they can,” Kaiser said. “If our tuition was at the same level as theirs, I can guarantee you we would do a zero. We’ve worked super hard over the past 10 years to keep tuition increases as low as possible.”

For Temple to not increase tuition, the commonwealth would have to restore funding back to its highest levels, he said.

In an audit of Penn State in 2017, Pennsylvania Auditor General Eugene DePasquale found that the university’s tuition growth was “outrageous,” and had increased 535 percent in 30 years.

DePasquale announced an audit of Temple on Aug. 30. DePasquale plans to look into the accuracy of the university’s academic statistics, capital projects, the effectiveness of Temple’s sexual harassment policies, background checks for employees and recent tuition increases. Temple was last audited in 2009, Kaiser said.

TEMPLE’S BUDGET MODEL

On July 1, 2014, the university implemented a new budget model called the Responsibility Centered Management. Discussions for a new budget began in 2010 before the 19 percent cut in allocations from the state went into effect.

This model allows each dean to have full autonomy of their budgets by determining how and where to spend their college’s money.

When the budget is initially calculated for the year, the university calculates how much revenue each school generates, which forms the basis for their budgets.

“[RCM] has been awesome for the university,” Kaiser said. “It really gives them the autonomy to run their operations rather than folks like myself or the provost dictating to them how to run things.”

The new budget model has incentivized deans to create new programs, which in turn generates more revenue and pressures deans to keep their costs down, Kaiser said.

There have been mixed reviews of the new model from deans, including Richard Deeg, the dean of the College of Liberal Arts.

“It really does give more control and managerial autonomy to the deans of the colleges,” Deeg said. “In the previous model, the president and provost would decide year to year what the budget for each college would be. That depended more on how well you could negotiate with the provost and the president and which college they favored at the time.”

Deeg said RCM incentivizes colleges to fundraise, think about how they can grow their revenues and forces deans to think about “the cost side of the equation.”

The downside of the model, however, is that it creates more competition among colleges to get credit hours, as more credit hours generates more revenue for the college, Deeg said.

“In my perspective, you want to keep student needs first and foremost,” he added. “We’re not about making a profit in colleges. It’s delivering what students want and need and doing it efficiently.”

Be the first to comment