Before his family fled Nazi persecution in Cologne, Germany, Fred Behrend’s father returned to a destroyed Jewish temple. He wanted to see if anything remained intact inside the burnt synagogue.

On his way out, he found a “yad,” a ritual pointer used to read the Torah, the main religious text in Judaism. He put it in his pocket for safe keeping.

More than 60 years later, Behrend watched his granddaughter use it while reading the Torah during her bat mitzvah, a Jewish tradition in which a girl becomes a woman.

“I had tears in my eyes when I sat next to her as she read her parashah [section of the Torah] with the yad my father took out of the burnt synagogue,” Behrend, 91, said.

Behrend has countless stories as a Holocaust survivor, and with the help of Larry Hanover, he was able to preserve these stories for generations to come.

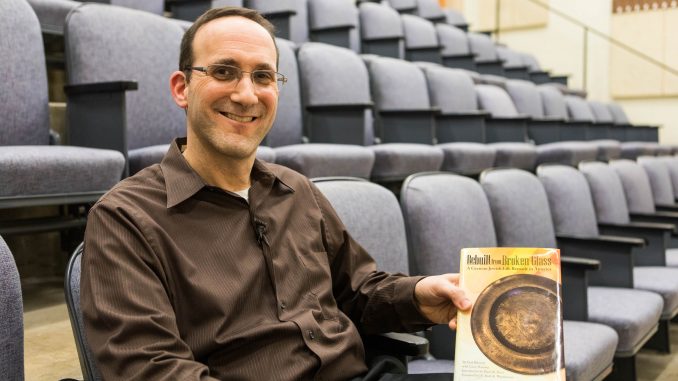

Hanover, an adjunct journalism instructor and 1988 journalism alumnus, spoke on Monday in Annenberg Hall about his book, “Rebuilt from Broken Glass: A German Jewish Life Remade in America.” Hanover helped write the memoir with the main subject of the book, Behrend, a Jewish native of Germany who left the country for Cuba before relocating to America nearly 70 years ago.

Holocaust Remembrance Day was recognized last weekend with numerous events and activities all over the world.

The book is written from the perspective of Behrend based on dozens of interviews with Hanover.

In 2010, Hanover met Behrend at Congregation Beth El, a synagogue in Voorhees, New Jersey. He was fascinated by Behrend’s stories after hearing him speak to Hebrew school students at the synagogue.

“He was so genuine,” Hanover said. “He had stories about the Holocaust, but he also had stories about everything else too, and he was just an incredibly warm guy and an incredible storyteller.”

Behrend and his family fled to Cuba after “Kristallnacht,” or the Night of Broken Glass, when anti-Semitic forces and German civilians destroyed the property of thousands of Jewish people throughout Nazi Germany in 1938. Nearly 100 people died.

Behrend was only 12 years old when he arrived in Cuba. The following year, he’d celebrate his bar mitzvah in Havana.

Hanover said the stories Behrend told about the cultural differences between Nazi Germany and Cuba were vivid. In Germany, Behrend lived behind a walled estate. He wasn’t able to have friends because his safety would be at risk.

“But when they got to Cuba, it didn’t matter anymore,” Hanover added. “You were safe.”

Hanover recalls a story about Behrend sharing a kite with a young Cuban boy in Havana. The boy put his hand out, and Behrend remembered his wonder at the one side of the boy’s hand being black and his palm being white.

Behrend said he’d never seen anyone who looked like that.

“It was little things like that, there was such a wonderment about him,” Hanover said. “It was his first friend.”

Starting in 2010, Hanover went to Behrend’s home in New Jersey during the summer to help him write and go over original documents and family chronicles that date back to 1490.

Behrend was surprised when Hanover said he wanted to help him write about his life. He spent his life selling air conditioning units in New York City. He never thought he could be a writer, but he knew telling stories about the Holocaust was important.

“I am always shocked and amazed when I find out how many people don’t know anything about the Holocaust,” Behrend said. “There are very few of us who are still alive and are able to tell our stories as representing what we went through.”

Per the advice of journalism professor Carolyn Kitch, Hanover sought support from a university publisher. The book was picked up by Purdue University Press and published in July 2017.

It was important to Hanover to attempt to verify Behrend’s 80-year-old memories. He used several documents from the U.S. Army and his passport when he left Germany for Cuba.

The book was peer reviewed by multiple people at Purdue and found to be authentic, Hanover said.

For Behrend, the book is more than just a comprehensive diary. He hopes his story also brings a message of resilience.

“It is important for people to understand the Holocaust, for no other reason than we are going through the same thing today in Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq,” Behrend said. “We have the same story all over again.”

“It’s unfortunate that the world never learns from its past,” Behrend added. “I would like to remind people of their past because it is being repeated again today.”

Be the first to comment