Plagiarism is never tolerated. But for poet Kenneth Goldsmith, it is always on the tip of his tongue.

“You should go steal questions from other interviews,” Goldsmith said. “I’ve got a thousand interviews online. Seriously, take the best one, and put your name on it.”

It’s not the most common advice, especially from a college professor, but in Goldsmith’s class at the University of Pennsylvania, students are directed to transcribe, plagiarize, thieve and appropriate, all in the name of learning to write.

And his works are no different.

“The old type of creativity really isn’t very interesting,” Goldsmith said. “So by being uncreative, you form a new type of creativity.”

“His approach to teaching is completely bizarre and pisses a lot of people off, including his students,” said Nick Salvatore, one of Goldsmith’s former students. “But by the end, everybody is really happy with it.”

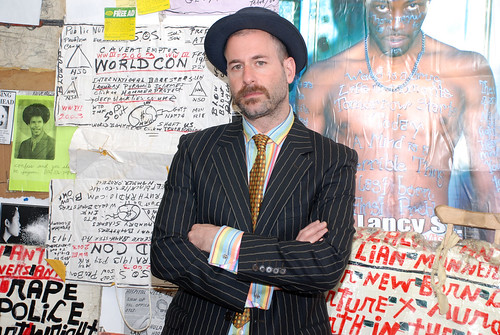

Goldsmith has made a life’s work out of representing the familiar in an unfamiliar context. His wardrobe is no exception.

Goldsmith’s handmade dark purple dress suit is covered with faintly colored hydrangeas. The ensemble matches his bright purple tie, striped purple shirt and purple fedora hat.

“I got into a fight with a couch, and I won,” Goldsmith said.

He’s just finished reciting a police interview and singing misunderstood lyrics at Temple University Center City campus as part of the university’s Poets & Writers series. It’s all part of the process he calls “uncreative writing.”

“If you look around at what’s held up as creative, most of the time it really isn’t,” Goldsmith said. “I don’t want to be that. I wasn’t always uncreative. I tried to be creative like everyone else. I failed. But it’s the failures that make things happen.”

And things have certainly happened.

Goldsmith is the author of 10 books of poetry. His most recent work is unofficially titled American Trilogy. It consists of “The Weather, Traffic and Sports,” which are respective transcriptions of a year’s worth of radio weather reports, a 24-hour traffic cycle and the radio broadcast of a Yankees game with the ads included.

Other works include a transcription of every word he spoke over the span of a week, every move he made throughout a 24-hour period and the retyping of every character from an August edition of the New York Times into a 900-page book.

“I write horrible boring books. No one should ever read them,” Goldsmith said.

He commonly refers to his following as a “thinker-ship” rather than a readership.

“Goldsmith takes the mundane and exemplifies the absurdity of language in certain contexts,” said Jackee Sadicario, a junior English and psychology major. “You never know how rhythmic the language of the weather reports are until you hear them chanted out loud.”

“Language is always poetic. We try too hard as writers,” Goldsmith said. “Who doesn’t understand a newspaper? Who doesn’t understand a ball game? They’re the dumbest things in the world. Everyone understands these things. They may wonder why, but they’ll understand the words.”

For those still unsure of how a traffic report could be transformed into poetry, Goldsmith broke it down even further.

“It takes regular language, and you hear it in a new way,” he said. “You hear the poetry in the everyday. “

“Initially, I found his work jarring,” Sadicario said, “but after a while, the rhythm of the traffic reports, the familiarity and repetition of the language becomes its own poetic device.”

When he’s not stealing others’ words, Goldsmith works on his other projects. Goldsmith is the founding editor of UbuWeb, an online archive of all things avant-garde. He is also the host of a weekly radio show on New York City’s WFMU-FM and a senior editor of PennSound, an online poetry archive.

“Look how easy it is to make a mark in literature,” Goldsmith said. “It’s a pathetic field we’re in.”

Yet the poet’s outlooks aren’t completely negative.

“There’s a new set of questions the next generation has to answer,” Goldsmith said. “You have to become a living, walking database for the language around you.

“It’s a beautiful problem to have, but you have to ask real questions about language. Dive into it, accept it, embrace it. Don’t try to be original – try to manage the language in an original way.”

“I’m through the hardcore uncreative phase,” Goldsmith said. “I could retype the world, but I don’t want to. I want things that are moving, exciting. I’m interested in the drama.”

Uncreative Writing, a book of Goldsmith’s own critical essays, is due from Columbia University Press later this year.

Jonathan Viguers can be reached at jviguers@temple.edu.

It’s a new take on what’s been going on for hundreds of years. I like it.

I support you .